Should I Use A Practice Record?

Ed Dumas

When I began teaching band, the idea of using a practice record was all about developing some marks to create that grade evaluation. I created a monthly or yearly calendar with plenty of little slots for students to fill in how many minutes they practiced each day.

Then, in about my fourth or fifth year of teaching, some bright little rocket scientist taught me how I needed to improve my practice record. With elementary band students who met with me twice per week, I always collected last weeks’ practice record data in the first class of each week. The second class each week was for students to turn in last weeks’ theory assignment. Both of those tasks usually took about 5 minutes or so while students were setting up.

Now one morning a nice young many showed me his practice record in which he claimed that he had practiced 2 hours and 20 minutes the previous week. His practice record showed a full 2 hrs and 20 minutes on a Sunday morning, and none for the remainder of the week. I asked him about that, and he explained that he just multiplied the 7 days times 20 minutes per day, and came up with 2 hrs and 20 minutes.

I then explained to him that, in the first year of playing, after the first 20 minutes or so, the body is tired and there is no benefit to practicing longer than that each day. The most important measurement, I said, was to practice OFTEN, and not necessarily LONG. Smart guy that I am, it did not take me more than a few more minutes to figure out that I was collecting the wrong information! (ie Frequency is more important than duration!)

From then on, I created practice records that counted the number of days in each week that students practiced, with a total possible at seven. Did this shortchange the students who practiced only 5 minutes per day, and called it a day’s worth? Not as far as I could tell. Students were no longer counting minutes and were spending more time being productive with their practicing. If anything, I felt that the practice record was now more of an incentive to do more, and of course, it was easier to understand.

Publisher’s Practice Records

In first-year band classes, most teachers use a method book such as Essential Elements or Standard of Excellence. That is well and good. These books, though, usually include a practice record inside the front or back cover, and I never found them useful. Due to the demands of publishing and printing, the dates on the practice record cannot be changed each year of publication. So, these books never include any dates at all, but rather something like “Week 1”, “Week 2”, and so on. Students that have tried to follow these practice records without dates easily get lost, as they are often unable to remember last week, never mind last month.

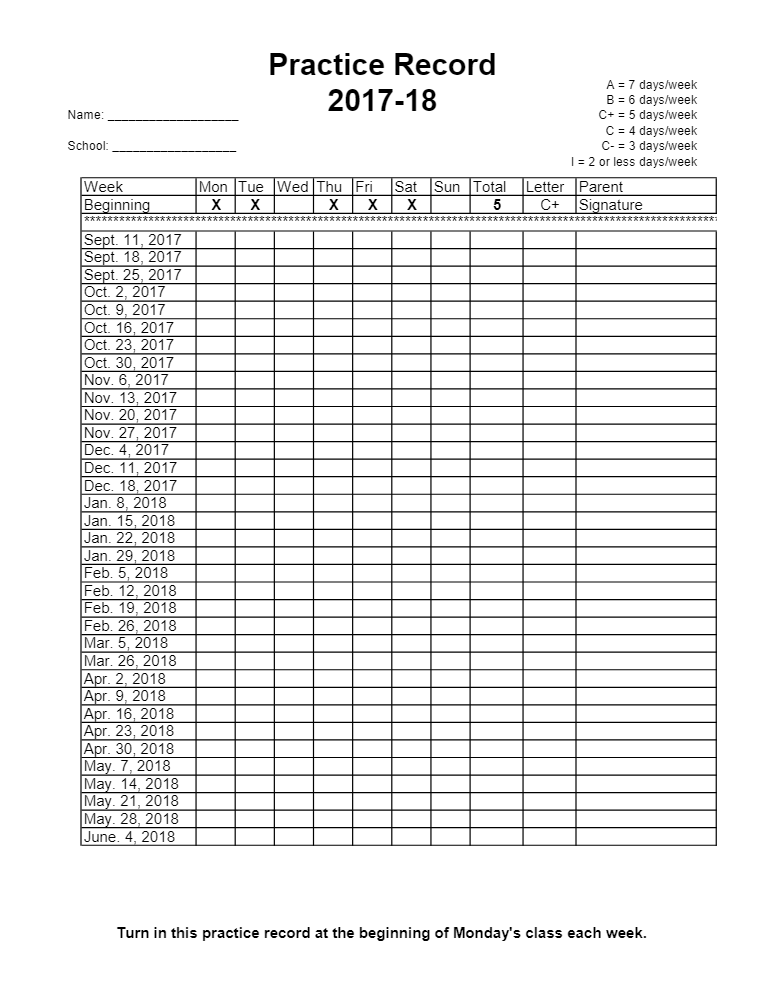

So, a suggestion for you would be to create your practice records with dates for the year, and tape this overtop the publisher’s practice record. Each day that the student practices, have them put an X in the correct box. At the end of the week, they can total it out of 7. If they practice twice on one day, they still get one X for the day.

The example below is of a practice record that I have created. Notice that the 6 Steps For Success are listed in the upper right corner. You can find out more about the 6 Steps in a previous blog entry.

Note that I have kept my practice record very neat and simple. Maybe it is just an “older man thing” but I am not at all sold on the fancy and busy ones that just provide more distraction. A simple practice record is easy to see trends.

Benefits of Using a Practice Record

Besides gathering up data for a report card, the practice record serves as a useful guide to students to show them how they are doing. Human memory is a fallible thing, and having a practice record with written down data does help students to see more clearly what their trends are in their work.

Some students believe that they are doing very well when in fact they are not practicing very often. Other students think they are doing very poorly when in fact they are doing very well by their practice record. These are the students that I feel benefit the most from using a practice record, for it allows them the chance to relax a bit in their success.

In the past when upper intermediate students were given a letter grade and percent for work in band class, using the data from the practice record was a good source of information. Of course, it should not be the only source but is a good set of data to include to show trends.

Today with letter grades disappearing, a simple practice record as above is still a valuable tool to show trends to students. After several weeks, even students in complete denial of their lack of work will see information that they have recorded, or not recorded. It can be a good illustration of how they need to improve their work habits to gain better success on the instrument.

One final thought for you about the practice record. Even though my practice record shows 7 days per week of practice as a possibility, I usually told my beginners to aim for 5 days per week as a good mark of success. There will always be those keeners who do more to earn 7 checkmarks in a week, but a natural target seemed better at 5. “One day of home practice for each day of school.”

But I would explain to my students the notion that success builds upon itself, and that those students who did 5 days of consistent practice per week would end up scoring an “A” in band class anyway. This usually happened because all their other scores were naturally higher due to their consistent work ethic.

These students would be “on top” of all the other aspects of their learning, such as theory assignments, playing tests and so on. This is the position that I wanted students to be in – in control of their playing and learning in the band, and enjoying the success immensely while just “playing the music.” In contrast, those that did little practice always seemed to be “behind” the class and struggling just to keep up simply for not knowing the instrument well enough. Given a choice, I would much rather be in the former group than the latter.

Fudging it on the Practice Record

There is much concern these days, and maybe rightly so, about students “fudging it” on their practice records. You know, putting down that they were practicing every day when in fact they hardly practiced at all. In my teaching, I could see this for myself, too. I had to wrestle with the idea of whether or not I should just scrub using a practice record because some students were not being honest about it.

In the past when upper intermediate students were given a letter grade and percent for work in band class, using the data from the practice record was a good source of information. Of course, it should not be the only source but is a good set of data to include to show trends.

Today with letter grades disappearing, a simple practice record as above is still a valuable tool to show trends to students. After several weeks, even students in complete denial of their lack of work will see information that they have recorded, or not recorded. It can be a good illustration of how they need to improve their work habits to gain better success on the instrument.

One final thought for you about the practice record. Even though my practice record shows 7 days per week of practice as a possibility, I usually told my beginners to aim for 5 days per week as a good mark of success. There will always be those keeners who do more to earn 7 checkmarks in a week, but a natural target seemed better at 5. “One day of home practice for each day of school.”

But I would explain to my students the notion that success builds upon itself, and that those students who did 5 days of consistent practice per week would end up scoring an “A” in band class anyway. This usually happened because all their other scores were naturally higher due to their consistent work ethic.

These students would be “on top” of all the other aspects of their learning, such as theory assignments, playing tests and so on. This is the position that I wanted students to be in – in control of their playing and learning in the band, and enjoying the success immensely while just “playing the music.” In contrast, those that did little practice always seemed to be “behind” the class and struggling just to keep up simply for not knowing the instrument well enough. Given a choice, I would much rather be in the former group than the latter.

Fudging it on the Practice Record

There is much concern these days, and maybe rightly so, about students “fudging it” on their practice records. You know, putting down that they were practicing every day when in fact they hardly practiced at all. In my teaching, I could see this for myself, too. I had to wrestle with the idea of whether or not I should just scrub using a practice record because some students were not being honest about it.

The result that I came to was that it was a minority of students who were less than honest on their practice record, and I did not want to take away the marks from the honest “A’s” because of a few “C’s.” Now there are a few caveats to that decision that you should be aware of.

First, I found that the majority of students who were less than honest on their practice record were mostly the later secondary school students. By the time they were in the senior grades, the stakes of a failing grade became pretty high which was a huge incentive for these students to fudge a practice record. To a large extent, I left that issue alone, as I did not want to see students fail either, just because of a lack of practice, but I will still tell them to practice!

On the other end of the timeline, I generally felt that the beginners were quite honest about the entries on their practice records. Maybe this was because I collected the information from those practice records from the beginners each week. As students were setting up, I would have them bring to me their practice records for the last week.

For the younger grades, there was a fair number of students who would practice at home reasonably, but forget to enter the information into their practice record. When it came time to gather the information, they would then have to “remember back” to get the credit. If I was collecting only one week’s worth of practice time, for beginners this was easier to do, and there would be less fudging of data. This was especially true if I was collecting days practiced, and not minutes practiced. This was triply true if we were using my practice records with dates on them, as students could not remember back more than one week to fill out a blank dateless publisher’s practiced record.

In short, you will always have some level of “fudging it” on the practice records. Not all of it is malevolent. But, some of it can be tempered with a better-designed practice record and better systems for collecting that information.

A Note On “Cheating”

In my first-year band classes, to discourage the “fudging it” problem on practice records, I would use a story that helped my students understand what the word “cheating” really means. I would make sure to be standing in front of the class when I started this story, and then ask them “I did a lot of bodybuilding when I was in my teens. Can you tell?” They would then be looking at me kind of blankly for a few seconds and I would say, “Yeah, neither can I, because I cheated.”

You see, in my teens, I was as tall as I am today at 6 feet even, though I weighed a mere 150lbs. I was like a snake standing upright. Today I am more like a snake who ate a mouse, so the students know full well that any bodybuilding I did was not successful.

The first reason for that was that we did not have all the fancy equipment of today. Back then we only had free weights. Bodybuilders today have access to gym equipment that locks them into position to complete only one kind of exercise, and physical cheating is simply not possible due to the design of the gear. For the next muscle exercise, you go to a new machine. The new system is far more expensive, but also far more successful.

Using free weights meant that you needed to be extremely knowledgeable and diligent about keeping all of your body muscle movements exactly correct. If you didn’t, you would lower the success of your workout. For example, doing arm curls with free weights meant that you must focus on only using your biceps as much as possible, and “locking out” any other motion throughout your body.

As a teenager, I did not know that I should not “swing” the barbell using my legs and butt to get the weights in motion. Doing so would put the effort into my legs rather than my arms. While I successfully lifted the barbell, the ultimate success of growing biceps was lost. This is what is called cheating – getting around the exercise and therefore defeating the positive results that were hoped for.

Students who heard this story could understand that the word cheating was not about being immoral, evil, wrong, and all the other high-value words placed on it. It was just that you got around the exercise and did not achieve the objective of the exercise. In terms of a practice record, it means we were not able to have an honest picture of how you are doing and what needs to change if anything.

Now, going back to what I said earlier in the article when I handed out the practice records, I would state to my students that 5 days of practice per week was their goal, not 7. I wanted students to recognize that they needed two days off from practicing like everyone else needs a weekend. As such, I would advise students that are doing too much practicing to back off a little to have a good life and not feel so stressed about their playing. This happened about as often as I told students who were practicing only once or twice per week to step it up a bit to not get left behind.

For these procrastinating students, it seemed that they took great comfort in knowing that there were respectable limits on how much time they were expected to put in on their own. The procrastinators could relax some in seeing me suggest to the “Type A Overachievers” to give themselves a break, and then know that I was serious about having some realistic limit on how much practice time they should do at home. The procrastinators seemed more ready to give it a decent try once that limit was established and noticeably visible in the classroom.

When students would bring to me a practice record for the previous week that was obviously fudged, I would ask them about it, but I would not make a big deal about it. Rarely would a student not tell me the truth to my face at that point. The best response here is to NOT talk about how wrong “cheating” is. Rather, talk about the need to get a clear picture of what is happening to best advise what to do next. If you take away the high stakes of practice records, they are less likely to feel a need to fudge it, either too high or too low.

Practice Record Bonuses

Back in the late 1990s, my teaching partner Denise O’Brien and I organized a trip of our band and choir students to Asakita High School in Hiroshima, Japan. To be fair, Denise was and is an amazing trip organizer who did all that work, and I just came along to wave the stick around! I warned our band students a full year before we left that they needed to start practicing hard every day because they will find the Asakita students are so talented that our musical efforts will be embarrassing. The response I usually got was along the lines of “Sure, sure, Mr. Dumas. It will all be okay.” “No, no, you don’t understand,” I would protest half-jokingly. “You can practice hard every day from now until the point we depart and they will still embarrass us. We just need to limit the damage!”

Well, when we arrived at the door of the band room at Asakita High School, the students were in the middle of a rehearsal. It only took a few minutes for my now slack-jaw students to understand what I was talking about. The Asakita students had now been in session for two weeks into that school year, and in that time had worked up a flawless performance of Shostakovitch’s Festive Overture!

Later after the rehearsal, I asked the band director through a digital translator how it was possible that her band was so good. The answer I got back from the translator was “I am sorry.” Quickly I realized that this simple question was going to take many smaller questions to understand a real answer.

You see, the band director believed that the band was not very talented by Japanese standards. I knew, on the other hand, that they were simply wonderful, but I still needed to understand more. So, after asking many hours of questions, I came to see that the answer was all about time on task. This band rehearsed every single day, doing 4 hours each school day from 3 to 7 pm, plus 8 hours on Saturday and another 4 hours on Sunday. That was a whopping 32 hours per week of rehearsal time!

Yet, soon I came to understand a more important truth. That is, those Asakita students were playing every day including Saturdays and Sundays, but they were not practicing at home because the Japanese houses were too small to accommodate it. So, I started to adjust my practice record again to reflect the concept of “Time on Task.”

Students now were encouraged to include any other playing time on their practice record other than their normal concert band class. That means they could add to the practice record other classes where they were playing, such as jazz band, or a lower-level concert band class as an aide. They could also add in outside-of-class sectionals, private lessons, small combos they played in, other bands such as cadets or the community band, or any event where they had “mouthpiece-on-face.” The idea was that the more often they played, the more they developed as musicians.

This practice of “time on task” on the practice record, significantly encouraged students to play in more groups, and it was noticeable that this was having a positive effect. Many students who used the bonuses practiced at home anyway, so I would not say that this caused students to not do studies on their instruments. But it certainly led more students to just get involved wherever they could, and this showed in their playing in the regular band class. I saw a trend that those students who played every day, regardless of WHAT they played, progressed much faster.

I would suggest to you that using a practice record to encourage more days of playing and performing anywhere and everywhere is a worthwhile use of the practice record. Your students will thank you for it with more great music coming back to you.

If you have other great ideas of how practice records can be used to help students develop their skills, I would love to hear from you. This is likely an ongoing topic that is worthy of revisiting once in a while, especially now that many students no longer receive a letter grade in band class.

Ed Dumas, B.Ed., M.A.Ed.